A television documentary team has pieced together details surrounding the case of a 16-year-old girl, executed two years ago in Iran.

Source: BBC

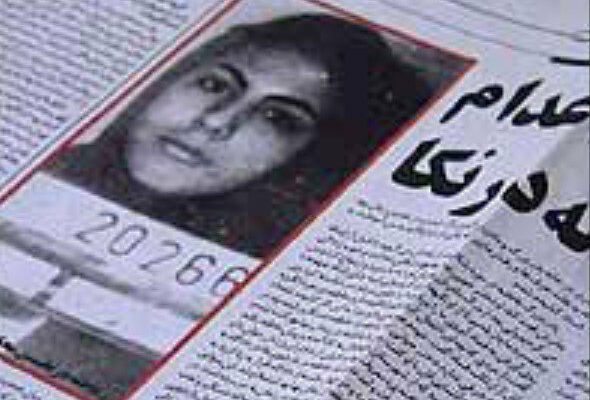

On 15 August, 2004, Atefah Sahaaleh was hanged in a public square in the Iranian city of Neka.

Her death sentence was imposed for “crimes against chastity”.

The state-run newspaper accused her of adultery and described her as 22 years old.

But she was not married – and she was just 16.

Sharia Law

In terms of the number of people executed by the state in 2004, Iran is estimated to be second only to China.

In the year of Atefah’s death, at least 159 people were executed in accordance with the Islamic law of the country, based on the Sharia code.

Since the revolution, Sharia law has been Iran’s highest legal authority.

Alongside murder and drug smuggling, sex outside marriage is also a capital crime.

As a signatory of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, Iran has promised not to execute anyone under the age of 18.

But the clerical courts do not answer to parliament. They abide by their religious supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, making it virtually impossible for human rights campaigners to call them to account.

Code of behaviour

At the time of Atefah’s execution in Neka, journalist Asieh Amini heard rumours the girl was just 16 years old and so began to ask questions.

“When I met with the family,” says Asieh, “they showed me a copy of her birth certificate and a copy of her death certificate. Both of them show she was born in 1988. This gave me legitimate grounds to investigate the case.”

So why was such a young girl executed? And how could she have been accused of adultery when she was not even married?

Disturbed by the death of her mother when she was only four or five years old, and her distraught father’s subsequent drug addiction, Atefah had a difficult childhood.

She was also left to care for her elderly grandparents, but they are said to have shown her no affection.

In a town like Neka, heavily under the control of religious authorities, Atefah – often seen wandering around on her own – was conspicuous.

It was just a matter of time before she came to the attention of the “moral police”, a branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard, whose job it is to enforce the Islamic code of behaviour on Iran’s streets.

Secret relationship

Being stopped or arrested by the moral police is a fact of life for many Iranian teenagers.

Previously arrested for attending a party and being alone in a car with a boy, Atefah received her first sentence for “crimes against chastity” when she was just 13.

Although the exact nature of the crime is unknown, she spent a short time in prison and received 100 lashes.

|

When she returned to her home town, she told those close to her that lashes were not the only things she had to endure in prison. She described abuse by the moral police guards.

Soon after her release, Atefah became involved in an abusive relationship with a man three times her age.

Former revolutionary guard, 51-year-old Ali Darabi – a married man with children – raped her several times.

She kept the relationship a secret from both her family and the authorities.

Atefah was soon caught in a downward spiral of arrest and abuse.

Local petition

Circumstances surrounding Atefah’s fourth and final arrest were unusual.

The moral police said the locals had submitted a petition, describing her as a “source of immorality” and a “terrible influence on local schoolgirls”.

But there were no signatures on the petition – only those of the arresting guards.

|

Three days after her arrest, Atefah was in a court and tried under Sharia law.

The judge was the powerful Haji Rezai, head of the judiciary in Neka.

No court transcript is available from Atefah’s trial, but it is known that for the first time, Atefah confessed to the secret of her sexual abuse by Ali Darabi.

However, the age of sexual consent for girls under Sharia law – within the confines of marriage – is nine, and furthermore, rape is very hard to prove in an Iranian court.

“Men’s word is accepted much more clearly and much more easily than women,” according to Iranian lawyer and exile Mohammad Hoshi.

“They can say: ‘You know she encouraged me’ or ‘She didn’t wear proper dress’.”

Court of appeal

– Atefah’s father

When Atefah realised her case was hopeless, she shouted back at the judge and threw off her veil in protest.

It was a fatal outburst.

She was sentenced to execution by hanging, while Darabi got just 95 lashes.

Shortly before the execution, but unbeknown to her family, documents that went to the Supreme Court of Appeal described Atefah as 22.

“Neither the judge nor even Atefah’s court-appointed lawyer did anything to find out her true age,” says her father.

And a witness claims: “The judge just looked at her body, because of the developed physique… and declared her as 22.”

Judge Haji Rezai took Atefah’s documents to the Supreme Court himself.

And at six o’clock on the morning of her execution, he put the noose around her neck before she was hoisted on a crane to her death.

Pain and death

During the making of the documentary about Atefah’s death, the production team telephoned Judge Haji Rezai to ask him about the case, but he refused to comment.

The human rights organisation Amnesty International says it is concerned that executions are becoming more common again under President Mahmoud Ahmedinajad, who advocates a return to the pure values of the revolution.

The judiciary have never admitted there was any mishandling of Atefah’s case.

For Atefah’s father the pain of her death remains raw. “She was my love, my heart… I did everything for her, everything I could,” he says.

He did not get the chance to say goodbye.