By Sophie Baron

Back in 2006, just as her career was heating up in Iran, a stolen video of her and her then-fiancé, Shahriar Shahamat, having sexual intercourse was disseminated across the country; in response, she and the fiancé were arrested. Although the two were soon released after it was determined neither had released the video, the actress was charged with fornication (Sex outside of marriage is illegal in Iran). She fled to France on the date her trial was supposed to begin. Sentenced in absentia to 90 whip lashings and a 10-year ban on working in cinema, the verdict essentially makes it impossible for Amir-Ebrahimi to ever return to Iran.

“The whole story is so absurd to me, that 15 years of a person’s life should be so transformed and made so difficult, they threw me out of my country because of my personal life, a thousand kinds of ugly acts were done to me, and then they ask me to forgive them? …I’m not in a position to forgive anyone,” she commented about the incident in a recent Persian-language interview with Radio Farda.

At first and for years after, Amir-Ebrahimi refused to comment about the video and how it came to be released to the public. In a 2009 interview, however, she revealed that the leaker was her former friend and fellow actor, Majid Bahrami. Bahrami, who died of cancer in 2014, had been sentenced to one-year imprisonment in 2007 for releasing the sex tape but was released after a few months due to deteriorating health. Amir-Ebrahimi stressed at the time that she would not “throw stones” at Bahrami, choosing instead to blame the situation on the regime judiciary.

Life in exile was not easy, as she soon discovered. “France was very unfamiliar to me for the first two or three years. Although I did a bit of theatre and small visual works, the cinema of each country has its codes and its own space, language and culture. The French language also greatly delayed my work because I did not speak French, and an actor is useless if she does not speak the language fluently. The French work environment is closed, especially for cinema, and getting into it was really hard work.”

Ethnic discrimination also played a role in making it difficult for her to find work. “There is also one negative point about European cinema for me: they seem to make a category for you, that you can only do one type of character. I mean, as a Parisian woman, I have French nationality, and I live in Paris, I have French friends, and I do the same things that the French do; but it’s scarce that I’m in French cinema …. Usually, if I receive a (film) offer, it’s from an immigrant.”

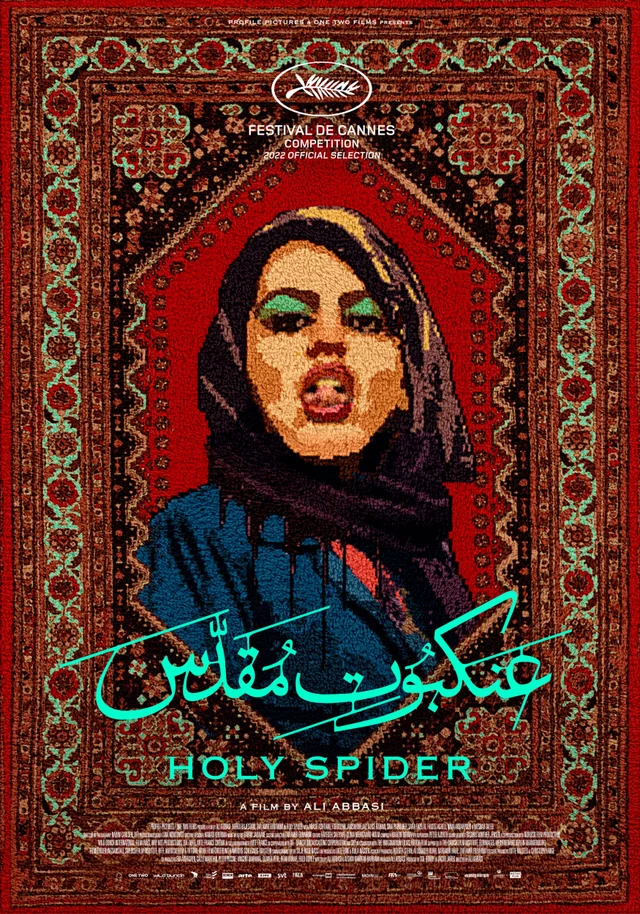

Holy Spider, the film for which Amir-Ebrahimi was awarded, is based on the true story of serial killer Saeed Hanaei, who killed 16 sex workers in Mashhad between 2000 and 2001. Hanaei asserted he had committed the murders because he was a devout Shi’a Muslim who wished to rid the city of “moral corruption.” Though he was ultimately executed, elements within the regime publicly expressed approval of his actions at the time. “Who is to be judged? Those who look to eradicate the sickness or those who stand at the root of the corruption?” the state-run Jomhuri Eslami newspaper had editorialised.

“I wanted to make a movie about a serial killer society. It is about the deep-rooted misogyny within Iranian society,” director Ali Abbasi said when describing his motivations for making the film.

For her part, Amir-Ebrahimi said that she wanted to be in the film after multiple Iranian female journalists told her they’d been sexually harassed and faced criminal punishment after reporting the harassment. “I couldn’t imagine that a journalist who reports a man for assaulting her can so easily become the target of assault herself,” she stated.

“I think this picture is very realistic. It is a dark film, but that is exactly what life is like in the Islamic Republic. Our problem in Iran is that we are afraid to talk about our problems. We don’t want the world to see them but the world itself is full of problems.” she added.

The regime has violently condemned the film, comparing it to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and stating that “it has insulted the beliefs of millions of Muslims and the huge Shiite population of the world”, and the Minister of Culture, Mohammad-Mehdi Esmaeili, threatened that any Iranians associated with the film would be criminally punished. Meanwhile, Iran’s former Empress, Farah Diba Pahlavi, a patron of Iranian cinema during the reign of her husband, the Shah, released a statement congratulating Ebrahimi and praising her activism on behalf of the Iranian people.

Despite the passage of time, and in response to claims made that Iranians living outside the country aren’t in touch with what’s happening on the ground there, Amir-Ebrahimi asserted that she is still very much an Iranian. “I am very close to Iran. Despite all the things that have happened to me, my relationship with Iran has never been severed. In fact, sometimes, I know more about what’s happening in Iran than my friends who still live there. That statement means ‘you are not in Iran and do not know what’s going on, I will not listen to you at all, and I do not want to hear you,’ but that is not the case. We see so many things better than those inside Iran can, primarily because we live in an open society and can see everything.

In her acceptance speech at the Cannes festival, the actress used her platform to highlight the current struggles of Iranian women and to praise other Iranian actresses working abroad: “This film is about women, about their bodies. It’s a film full of hate, hands, feet, breasts, gender, everything that is impossible to show in Iran. I know the difficulties Iranian women face every day,” before going to praise “her sister Golshifteh,” the actress Golshifteh Farahani, who was one of two other Iranian women who had also been nominated for an award at Cannes.

She also expressed her support for the recent protests in Abadan, where people have taken to the streets to decry regime corruption after a shoddily built apartment complex collapsed and killed 41 people. “Although I’m thrilled at this moment, part of me is sad for the people of Iran who are grappling with many problems daily. I’m here, but my heart is with the women and men of Iran. My heart is with Abadan,” Amir-Ebrahimi noted.